*This article is part of the TOK Roadmap — a visual, all-in-one guide I created to help you ace Theory of Knowledge. [View the full roadmap here.]

In this post, I explain

- What are Knowledge Questions?

- The Knowledge Framework

- Should I study Knowledge Questions?

I told you in the ‘What is TOK’ article that TOK is all about asking questions. If you learned a formula in math class, you’re encouraged to question how it was created, why we accept it as true, etc. If you learned about a famous event in history, you are encouraged to question your beliefs, bias, and understanding of evidence.

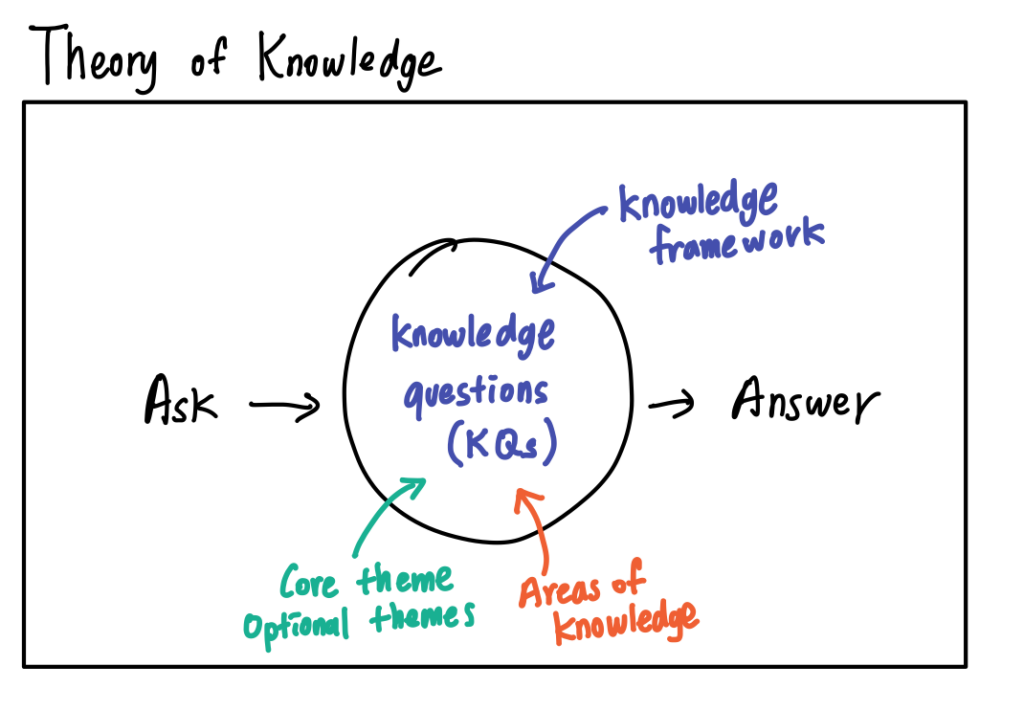

Questions you ask or answer in a TOK class are called knowledge questions (KQ). Really, this is what you do in TOK for two years.

The bits in different colors are just tools to help you narrow down the asking and answering, so that the questions are more manageable.

So what are Knowledge Questions?

TOK requires a KQ to meet these three standards. A KQ should be:

- about knowledge (of course)

- should involve knowledge in general, not just subject-specific content—if you ask “What were the major events leading up to World War I?” you are asking a specific history question that gives you factual knowledge, but it isn’t about knowledge itself (you’d find answers in a textbook but probably wouldn’t question them).

- contestable

- open-ended, should have more than one answer — again, for that question, you’d just get a list of significant events.

- related to TOK concepts

- You will encounter TOK concepts naturally as you explore sample knowledge questions, like interpretation, bias, values, etc.

Following this principle, how can we improve “What were the major events leading up to World War I?”

Maybe, if we recognize that different textbooks provide different information on what really led to WW1 (there are short and long term factors, which makes this really complicated), we can ask, “to what extent does the selection of historical events in textbooks reflect cultural or political bias?” We may even go further and ask, “what makes some textbooks more reliable than others?” and “what makes a textbook, a textbook?”

These questions are contestable. They don’t have the word “knowledge” in them, but still deal with aspects of knowledge—using many keywords like ‘culture’, ‘bias’, and ‘reliability’ that make us question how the value we attach to knowledge can change based on these subjective concepts.

Let’s think one step further.

Imagine you are actually answering these questions on a piece of paper. Would you refer to philosophical thinkers or theories about knowledge from textbooks to answer it? No—instead you need to come up with specific evidence/real-world examples (maybe a pair of textbooks you can compare).

TOK forces us to broaden our narrow questions, but requires us to answer these broad questions with specific, narrow evidence/examples.

Knowledge Framework

IB provides a Knowledge Framework to categorize KQs, and with it brings a whole bunch of TOK terms.

The framework essentially demands that a KQ should deal with how knowledge is defined, perceived, created, or evaluated.

Defined: The ‘scope’ of knowledge—what counts as knowledge? what questions does the knowledge answer or create?…

Perceived: The ‘perspectives’ surrounding knowledge—How do our values and bias affect what we know?…

Created: The ‘methods and tools’ for producing knowledge—what tools or methodologies do we use to create knowledge? What instructions do we follow or create to make knowledge?…

Evaluated: The ‘ethics’ of knowledge—is some knowledge unethical to pursue? Should we regulate what kinds of knowledge we seek? Do we, as humans, have any responsibilities for knowing something?…

“values” “perspectives” “bias” “methodology” “ethics” “responsibility” —these are all TOK terms. I don’t like listing or memorizing these terms because you will encounter them naturally by looking at/asking/answering knowledge questions.

Should I study Knowledge Questions?

You might ask, and for good reason, “shouldn’t I make a list of these TOK terms in KQs and study each of them in detail?”

I understand you—you might feel like you’re not learning something in TOK if you don’t study things formally.

And yes, you can look up definitions of these terms if you need to, but I’m very much against formalizing these concepts into one locked definition.

This not only defeats the whole purpose of TOK, but also might not be useful at all when it’s time to do the assessments. Consider the simple word “ethics”—what we consider ‘ethical’ differs by area of study, specific discipline, and specific scenarios.

It’s best to learn TOK terms through these specific scenarios—an example-by-example method where you practice doing TOK by finding real-world examples that answer a KQ. (Ideally, your class should provide these opportunities.)

So, if you want to practice TOK on your own, I suggest picking a KQ and answering it with an example—can be your own experience, or something you find online.

Updated: April 9, 2025

Leave a Reply